SYMPOSIUM

Mosses and Lichens

4 July 2020

In English

The gathering will happen through the internet platform called Zoom.

In order to participate, please register in advance under this link:

https://zoom.us/meeting/register/tJcsduirqTouGNWmVKmZSxHCEFiS8hQ5ioM0

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

4 - 5 p.m.

Urszula Zajączkowska

On mosses - plants without skin

6 - 7 p.m.

Michael Marder

Moss: The Inassimilable

8 - 9 p.m.

Laurie A. Palmer

The Lichen Museum

In every way mosses could seem plain, dull, modest, even primitive. The simplest weed sprouting from the humblest city sidewalk appeared infinitely more sophisticated by comparison. But here is what few people understood, and what Alma came to learn: Moss is inconceivably strong. Moss eats stone; scarcely anything, in return, eats moss. Moss dines upon boulders, slowly but devastatingly, in a meal that lasts for centuries. Given enough time, a colony of moss can turn a cliff into gravel, and turn that gravel into topsoil. Undershelves of exposed limestone, moss colonies create dripping, living sponges that hold on tight and drink calciferous water straight from the stone. Over time, the mix of moss and mineral will itself turn into travertine marble. Within that hard, creamy-white marble surface, one will forever see veins of blue, green and grey – the trace of the antediluvian moss settlements. St. peter’s Basilica itself was built from the stuff, both created by and stained with the bodies of ancient moss colonies.

Moss grows where nothing else can grow. It grows on bricks. It grows on tree bark and roofing slate. It grows in the Arctic Circle and in the balmiest tropics; it also grows in the Arctic Circle and in the balmiest tropics; it also grows on the fur of sloths, on the back of snails, on decaying human bones. Moss, Alma learned, is the first sign of botanic life to reappear on land that has been burned or otherwise stripped down to barrenness. Moss has the temerity to begin luring the forest back to life. It is a resurrection engine. A single clump of mosses can lie dormant and dry for forty years at a stretch, and then vault back again into life with a mere soaking of water. (…)

Somewhere between Geological Time and Human Time, Alma posited, there was something else – Moss Time. By comparison to geological Time, Moss Time was blindingly fast, for mosses could make progress in a thousand years that a stone could not dream of accomplishing in a million. But relative to Human Time, Moss Time was achingly slow. To the unschooled human eye, moss did not even seem to move at all. But moss did move, and with extraordinary results. Nothings seems to happen, but then, a decade or so later, all would be changed. It was merely that moss moved so slowly that most of humanity could not track it

Elizabeth Gilbert, The Signature of All Things, Bloomsbury, London 2013, pp. 197 and p. 199

4 - 5 p.m.

Urszula Zajączkowska

On mosses - plants without skin

Urszula Zajączkowska’s talk will be based on her text “Wet rugs” from the book “Patyki, badyle” (“Sticks, stalks”), in which she reflects on bryophytes – small, herbaceous plants that grow closely packed together in mats or cushions on rocks, soil, or as epiphytes on the trunks and leaves of forest trees. Bryophytes form one of the oldest group of plants on our planet – they evolved more than 500 millions years ago and barely changed since that time. This group of plants comprises three separate evolutionary lineages, which are today recognized as mosses, liverworts and hornworts.

Urszula Zajączkowska is a poet, botanist, visual artist and musician. She currently works as an assistant professor at the Autonomous Department of Forest Botany at Warsaw University of Life Sciences where she studies growth, anatomy and movement of plants, involving their aerodynamics and biomechanics. For her writings - two volumes of poetry: “Atomy” and “Minimum” as well as the book „Patyki, Badyle“ she received numerous prizes and prize nominations. As a visual artist, she creates short films, for example Metamorphosis of plants (https://vimeo.com/161297124), inspired by the work of Johann Wolfgang Goethe. The movie combines scientific films recording plant movements with the dance of the national ballet soloist Patryk Walczak. It won the Scinema Festival of Science Film in the category of Best Experimental Film / Animation.

6 - 7 p.m.

Michael Marder

Moss: The Inassimilable

Moss is as unlikely to fascinate philosophers as, say, cockroaches or dust. But if we scratch the surface of that indifference, something else entirely seems to be hiding just beneath it. Each in his own way, Francis Bacon, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Friedrich Nietzsche tell us one and the same thing: moss is inassimilable to metaphysics. Condensing in miniature the entire kingdom Plantae, these tiny plants comprising approximately 14,000 species throw a formidable challenge to thinking based on oppositions, to linear chronologies, and to conventional theorizations of energy. From the outside, they support projects that aim to revolutionize philosophy, to convert philosophy back to life from its obsession with death. Seen through a child’s eyes, moss becomes as cognitively fresh and refreshing as it is vividly, dazzlingly green.

Michael Marder is Ikerbasque Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU, Vitoria-Gasteiz. His work spans the fields of environmental philosophy and ecological thought, political theory, and phenomenology. He is the author of many books and countless academic articles that engage with a critique of anthropocentrism in philosophy accounting for non-human types of existence especially with respect to the ontology of plants and their modes of being. His most recent publications include: Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013); “The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium” (2014); “Pyropolitics: When the World Is Ablaze” (2015); “Dust” (2016); “Grafts” (2016); with Luce Irigaray, “Through Vegetal Being” with Luce Irigaray (2016); and “Energy Dreams: Of Actuality” (2017), Political Categories: Thinking beyond Concepts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019)

8 - 9 p.m.

Laurie A. Palmer

The Lichen Museum

The Lichen Museum is an inside-out institution vastly distributed across diverse surfaces of the earth, locally experienced and multiply constituted. As an ongoing collaborative art project (in collaboration with lichens), The Lichen Museum aims to expand human understandings and experiences of time, to think more broadly about our relational selves, about ecological collectivities and the violence of privatization, and to counter rhetorics of scarcity, fear and competition with a visceral sense of potentiality and possibilities for change.

While museums are defined as institutions that care, western museums of art and natural history are known to still house both beings and things that were captured, stolen, or killed in the project of colonization and empire-building, and to organize their collections following hierarchical and exclusive notions of order and value. The Lichen Museum borrows the museum framework of “caring for,” but is not structured by practices of acquiring, possessing, enclosing, or preserving (nor does it charge admission). Instead, its “collection” is massively distributed, freely accessed, always open, and remains in place. The Lichen Museum re- values “slow,” “small”, “incremental,” “resistant,” “persistent,” and “surprising” — in contrast to the spectacular, and to universal and totalizing predictions of apocalypse (or rescue).

In her presentation the artist will describe The Lichen Museum through brief summaries of the seven chapters of a book she is writing about it. Each chapter (Massively distributed, More than one, Lichen time, In place, Likeness, Usefulness, and Sun) explores a radical quality of lichens. As anti-capitalist companions and climate crisis survivors, lichens suggest alternate possibilities for human being and relating.

Palmer find permission and inspiration in the work of many other writers, researchers and artists whose work cuts the world into unexpected shapes, inspiring the rest of us to disrupt naturalized reality in order to propose and invent alternate futures.

Laurie Palmer is a Professor in the Art Department at UC Santa Cruz. Her place-based, research-oriented artworks take form as sculpture, public projects, and artist books, and she collaborates on strategic actions in the contexts of social and environmental justice. Her book In the Aura of a Hole: Exploring Sites of Material Extraction (2014, Black Dog) investigates what happens to places where materials are removed from the ground, and how these materials, once liberated, move between the earth and our bodies. She is currently working on The Lichen Museum, a book that envisions lichens as anti-capitalist companions and climate crisis survivors. Palmer has shown her sculptural work most recently at: The Museum of Art and History in Santa Cruz (Beyond the World’s End, 2020); Haus der Kunst in Munich (The Big Sleep, 2019); Iceberg Gallery in Chicago (Sensing Connection to the Time Left, 2018) and Gallery D21 in Leipzig (Schichten, 2016, curated by Lena Von Geyso and Elisabeth Pichler).

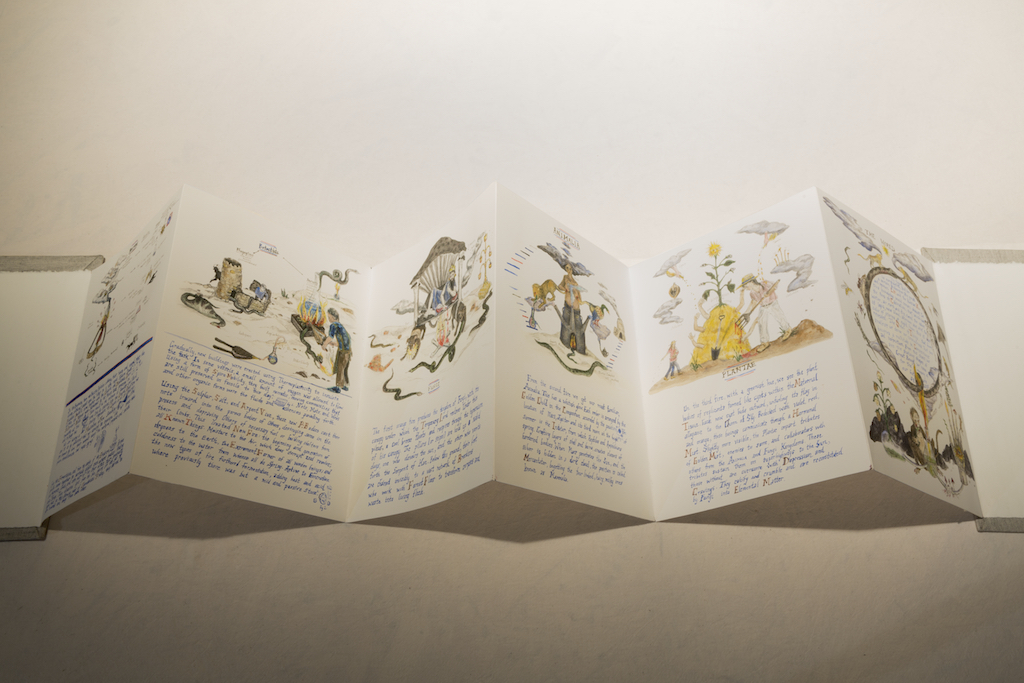

Image

Candice Lin: 5 Kingdoms (Book), 2015

Photo: Tamara Lorenz

(More images: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1R9bvUyMSSv79JBxJHbork6Vn9l4l0eJq?usp=sharing.

Presented in the exhibition “Floraphilia. Revolution of plants”, until 20.09.2020)

An event as part of the exhibition "Floraphilia. Revolution of plants" in collaboration with exMedia Lab, Academy of Media Arts Cologne