JOURNEYS THROUGH THE STORAGES OF IMAGINED REALITIES BACK TO THE ARCHIVE OF THEIR POSSIBILITIES IN THE WORK OF BRADLEY DAVIES

Annelie Pohlen

An essay on the exhibtion "Bradley Davies: Hold Your Horses"

From realms that once meant the world, the horse has made off. In search of a meaningful existence in the here and now, it has risked the transformation into a creature of the same name from the world of modern competitive sports, to sprawl out on the ground of a possibly more suitable arena. Its owners, no less out of time, still wield their chivalrous weapons as if they simply did not want to admit that the horse that carried them from victory to victory in heroic times is now courting for attention on other fields. Yet, Bradley Davies' bizarre transformation of its former greatness does not promise unadulterated enjoyment in the competition between man and beast. The horse's legs, not entirely insignificant parts of a once glorious existence, now placed next to its torso appear merely as sculptural crutches. And, it seems, nothing will free them from their sublime rigidity—neither the lulling sound collage of snorting, neighing and hoof stamping from the "Arena" of the Cologne City Soldiers nor the new edition of the "Memoirs of Dick, the Little Poney", which charms the senses as well as the spirit. And why should a "Little Poney"—whether in the fake exquisitness of the accompanying booklet or in the performative appearance of its "creator" on the stage right next door—pay even the slightest attention to these descendants of the once heroic creature. As they, together with their chivalrous rider, have now landed on the lowlands of the floor and the unglamorous battlefields of ironing boards. Especially since Bradley Davies has immediately redeemed his creatures bred for the art space, along with their sporty descendants, from everything sacred to their new gymnastic users. Stripped of its legs, his horses can at best pass for a leather-upholstered bench.

For its appearance at the Temporary Gallery, a door handle attached with a banal plastic cord is emblazoned on the invitation. Bradley Davies' horse can be reined in where knights and cowboys used to tie up their proud companions, even without leather reins. Those who are uncomfortable with the plastic cord used for the entrance will feast on the nobler materiality of its other harness. Its relics, charged with diverse spiritual and sensual fantasies of redemption, are embedded in the wall of the exhibition room within sight of the stranded horses.

Some of its prehistoric owners have moved into the Temporary Gallery's staged storage facility—right after their glamorous appearance in the city with the symbolic name of Siegen. Backstage, as it were, they are now resting for an indefinite period in intimate and peculiar company with various props of art and mundanity, history and the present. One can first overlook them after the many previous appearances of these meandering shadows of highly equipped 'iron men'. For their changing surroundings, Bradley Davies provides the rather artfully converted stages from case to case to suit the given location.

This is possibly due to his particularly subtle understanding of what is called 'site-specific' in the language of art contexts. And so the icon of his present hometown Cologne comes into play in the Temporary Gallery. Even for Bradley Davies, who was born in the still proud center of a former world empire, there is no way around it. Which is why an incident reported by the Cathedral's own radio station for historical as well as tourist amusement, according to which the Napoleonic troops converted the venerable Cologne Cathedral into a horse stable during their conquests, immediately settles into Bradley Davies' material box. The emperor, inclined to the soldierly and the secular, could be expected to do so. And today it provides the British artist, who is obsessed with history(s), with a template for all kinds of enigmatic loops of thought—between the physical materials of the exhibition in space and their inventions in text, image, writing, color and sound, filtered from many historical events and now radiating in all directions.

And just as the French ruler galloping across the territorial borders left behind in proud Cologne among the resistant citizens rites both thoughtful and carnivalesque, so too did the protagonists of the legendary Battle of Hastings crossing the English Channel from continental France. The islanders called to order there finally ended up in a roundabout way via the no less legendary tapestries of Bayeux in the trove of Bradley Davies, who had traveled back from the island to the continent.

It is obvious that the saying "iron out your battles" had to incite the artist, who juggles with thoughts, words, texts and images: Which is why, in ironing out the consequences of the war between the successful William the Conqueror and his insubordinate henchmen, he catapults the more or less occupied appearances of the combatants in the embroidered tapestries onto the truly mundane battlefield of ironing boards in a rather less noble, yet brilliantly deceptive technique. Which, as a daring collision between reverence for the out-of-time heroes and disgust at their irreverent placement, may well trigger incalculable reactions in the audience, the author of this text included.

"Signalstörung" (signal interference) was the title of the exhibition staged in Siegen almost simultaneously with "Hold Your Horses". There, a handsome array of these heroes, ironed out by means of painting, has landed on the floor and walls of the Kunstverein. Most of them are folded up, thus somehow legless like Bradley Davies' horse, but all of them portrayed as individuals who have become legends and are recognizable in their cultural and historical splendor. What in Cologne serves as an artful blending of the disdainful exploitation of the sacred place by the space-filling sound of the carnival knights defying it to this day, in Siegen the contact microphones placed on both sides of the former shop-window front offer no less site-specificity as inwardly and outwardly directed mediators of the water- and wind-based sound collage "looking through the hearing glass". These are messages from everyday life, the all too rude consequences of which have been escaped for the time being in the protected zone of the Kunstverein. Bradley Davies has thus also given the protagonists of the historic Battle of Hastings, which survives as a Unesco World Heritage Site, another chance in his conceptual cosmos of ceaselessly circulating image/word condensations.

In Siegen, the tour leads through the assembly of simulants executed in perfect trompe-l'œil painting to a detailed photograph of an archaic lighthouse lens from the world of warning and surveillance, rather discreetly interspersed in the staging and painted in precisely this technique. In Cologne, the undercooled brilliance of three counterparts demands the audience's attention right from the entrée. Which is why the enigmatic playfulness with the possible associations between the individualized light of the lenses in "Scale Electric," "Rainbow Warp," or "ZoOom" and the arrangement of the enclosed sunflowers on the floor, lurching on the border to the bizarre, catapults the perception of the space into a strange obliquity.

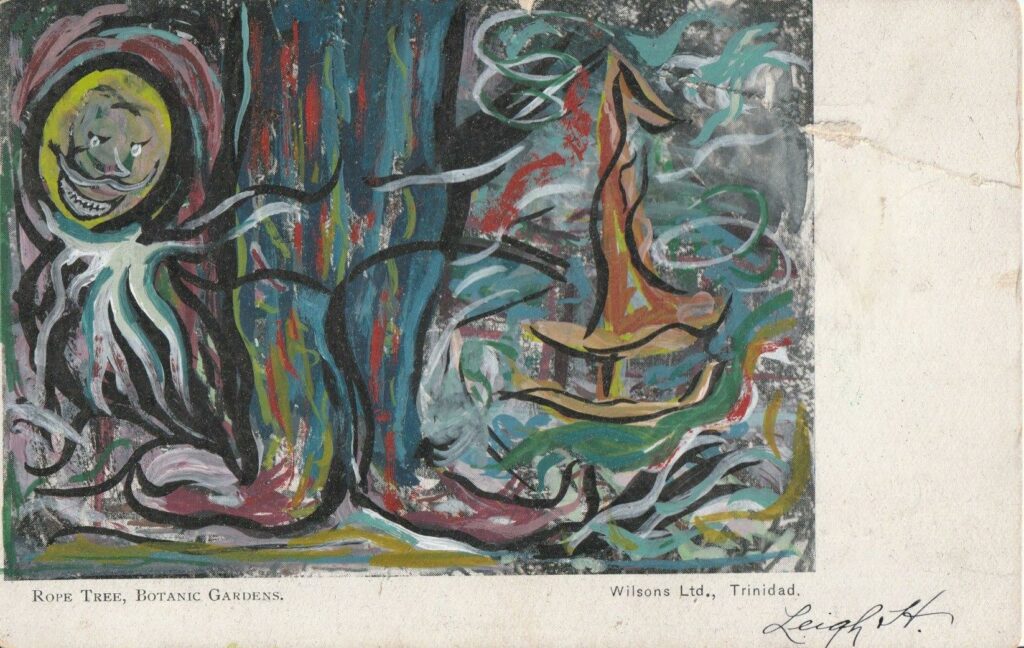

"What Juju? In the Botanic Gardens" is the title of one of the wonderfully subversive postcards that Bradley Davies made available to the GAK in Bremen as an annual gift in 2019. As expected, his postcards, done in the best watercolor and gouache techniques, captivated the art-minded public to such an extent that his offering was soon sold out. "He is interested in the deviations and flaws in the mass-media image, the meanings of which he charges through cropping and repetition, the selection of his artistic materials, and his handling of the work, often disguised as a joke."1 So or similar are many attempts at interpretation, to which the author of this text certainly subscribes. In Davies' historical graphic, appropriated for the postcard, a wildly masked ghost swings through the exuberant growth of a botanical garden on the endless loops of a rope tree. "In a general sense, the term 'juju' can be used to refer to magical properties dealing with good luck ... 'Juju' is a folk magic in West Africa ... Juju charms and spells can be used to inflict either bad or good juju ... It is neither good nor bad, but it may be used for constructive purposes as well as for nefarious deeds."2 Significantly, on another postcard from the episode in question, two white horses have carried a young woman and her companions to a white sand beach by a blue sea. Where the saddle is, Davies has painted a red rose each. The lady dismounted, her companion did not. Which is why the presumed lover disappears behind the love flower. The scenario is called "New Romantics".

To free readers of this text from potentially all too confusing, if not even devious thought loops: The author simply follows an artist's enigmatic pleasure in puns, yes—even those that the art connoisseur who considers himself educated may consider a rather blatant, or at least creepy, imposition. It should be expressly noted here that their spark, together with their more or less suitable flashes of inspiration, may ignite with a certain delay—as was the case with the author herself.

Processes of seduction via the pretense of supposed realities are by no means an invention of highly intellectual cultural representatives, even though the legend of the painting artist Zeuxis of Heraklaia from pre-Christian times can be interpreted in this way. In antiquity, the art of deception was still regarded as a demonstration of man's superiority over the animals that were bent on Zeuxis' grapes. Although this has long been in question, this ability is held in the highest esteem by the community of cultural citizens disturbed by all kinds of destructive processes in contemporary art. And this probably in spite of, or precisely because of, some irrevocable realities: The further the alienation of the perceiving human being from the supposed object of perception, which was formerly called reality, progresses, the more multifaceted the palette of human striving for appropriation through imitation becomes—in everyday life as well as in art.

Perhaps it is daring, but perhaps appropriate, to understand Bradley Davies' 'signal disturbance' as a conceptual focal point in the confusing network of his artistic examination of a reality beyond the obvious. After all, it is ultimately about unstoppable turbulence as a consequence of disappointed expectations. And what could be more appropriate than the technique of deceiving the perceiving eye, which has been admired since time immemorial, in order to finally trace the deception of thinking via the deception of all senses. And yet to have fun with the "roles we perfect for the setting of society. Stories we tell, games and music we play, I read with a love of poetry as a mesh of absurd comedy or satire. For me, masquerade is a means of approaching these phenomena."3

What the painting signal disruptor, with perfect command of his means, now presents with subversive bravura as what it is in his ceaselessly circulating conceptual cosmos: a possibility that in itself is as useless as painted grapes for the birds or as lenses of lighthouses for a sunflower field in the entrance of the Temporary Gallery. Just as little, by the way, as the blue paint, the brilliance of which Bradley Davies' is dispersed in the storage harboring the ironing board heroes, frees the former garage door from its heaviness. And yet: as beautifully subversive as the postcard of the "New Romantics" stored on the internet can be precisely the ideas of unfinished utopias from the timeless and placeless archives of an unflinching, perhaps even post-romantic storyteller, defying the radiant pretenses.

Notes:

1— Jahresgaben Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst, Bremen

2— aus dem in diesem Kontext außerordentlich inspirierenden, weil unabgesichert facettenreichen Autorenlexikon in Wikipedia. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juju)

3— Bradley Davies anlässlich der Verleihung des WERK.STOFF Preises für Malerei der Andreas Felger Kulturstiftung und des Heidelberger Kunstvereins, 2021

Annelie Pohlen (*1944) lives and works in Bonn. From 1986 to 2004 she was the first permanent director of the Bonn Kunstverein. She has published her texts in Artforum, Flash Art, and KUNSTFORUM International, among others. In 2018, she was awarded the Rheinlandtaler of the Landschaftsverband Rheinland, together with Renate Puvogel, for her many years of regional and international work for contemporary art.

Images

1/2 — Bradley Davies: instable, 2022

3 — Anon.: Memoirs of Dick the Little Poney; Supposed to be written by himself; and published for the Instruction and Amusement of Good Boys and Girls, London 1800, J. Walker, No.44, Paternoster Row; and sold by E. Newbery, Corner of St. Paul's Church-Yard

4 — Memoirs of Dick, the Little Poney. A live audio drama with Bradley Davies and Friends, 2022, Temporary Gallery

5/6 — Bradley Davies: Looking through the hearing glass, 2022, Signalstörung, Kunstverein Siegen

7 — Let's comet, 2019

8 — What Juju? In the Botanic Gardens, 2017

9 — Rainbow Warp, 2022

10 — ZoOom, 2022

11 — New Romantics, 2019

Photos:

1, 2, 6, 8, 9 — Tamara Lorenz

4 — Lina Parisius

5, 6 — Simon Vogel

7, 10 — Courtesy: GAK Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst e.V. / der Künstler